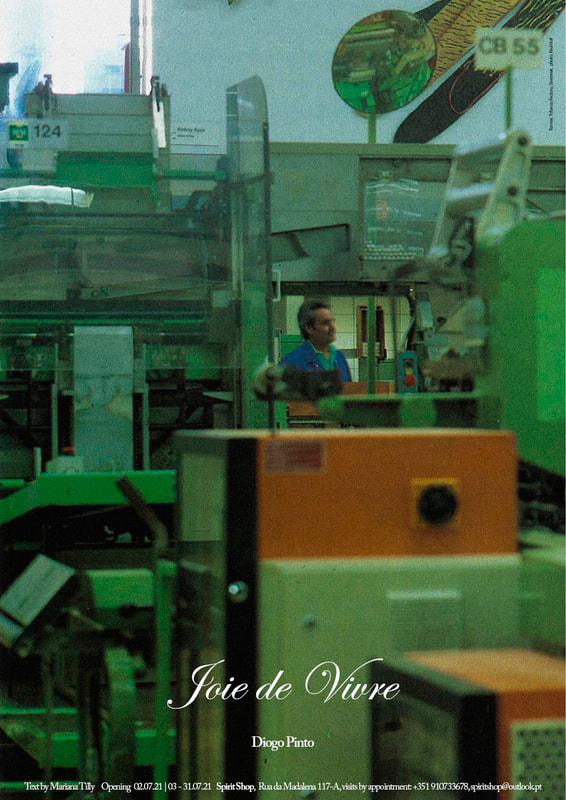

Joie de Vivre

Diogo Pinto

03.07—31.07.2021

Diogo Pinto

03.07—31.07.2021

Views of the exhibition Joie de Vivre. Photos: Beatriz Pereira.

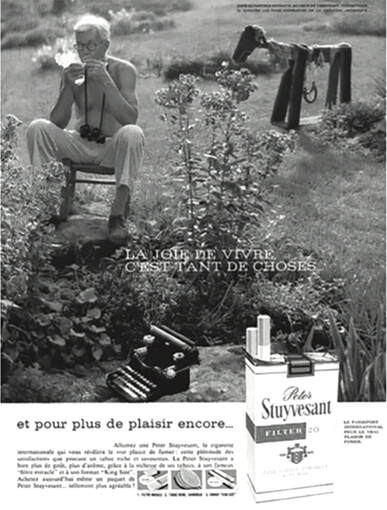

Take a moment to analyse the picture above. I know, I know...: ahead of you, two beautiful spaces filled with bright, sensual paintings are calling out. But first, please consider this shady print of a Peter Stuyvesant Cigarettes poster from 1962. It states, nonchalantly,

La joie de vivre, c’est tant des choses...

Typewriter resting on a rock, the artist takes a break; inhaling Stuyvesant pleasure, exhaling countryside glory. He’s retired; plenty of space to enjoy the golden years. The ad makes a good point though: joy is many, many things. Here’s the scope of it:

In 1960’s spring, the Turmac Tobacco Factory (located in Zevenaar, Netherlands) became the setting of a happy and peculiar event. Paintings were commissioned to emerging European artists within the framework of an experimental cultural project, pushed by semi-public institutions working backstage, and funded by the European Foundation for Culture. The commissioned paintings were to be made specifically to be installed within the factory, and created under the theme Joy of Living. The idea had come from the factory president, Alexander Orlow, who leaded and gave face to the experiment, becoming somewhat of an art-lover socialist hero (imprinting the mythical status ascribed to corporate founders – more on that later – and closely advised by Willem Sandberg, then director of the Stedelijk Museum). The point was not only to bring contemporary art closer to the factory workers, but to improve the environment within the post-war, severe, noisy and industrial production halls where hundreds of workers produced the Peter Stuyvesant Cigarettes. Absolute requirements for the artworks were a considerable size and powerful colouring, in order to “raise spirits of people engaged in monotonous factory work” (1). Indeed, Orlow did an amazing job, and the experiment proved a success - the paintings were dramatically hung in panels from the ceiling of the halls overnight, surprising workers the next morning. Over the following decades, the collection grew into the famed Peter Stuyvesant Collection.

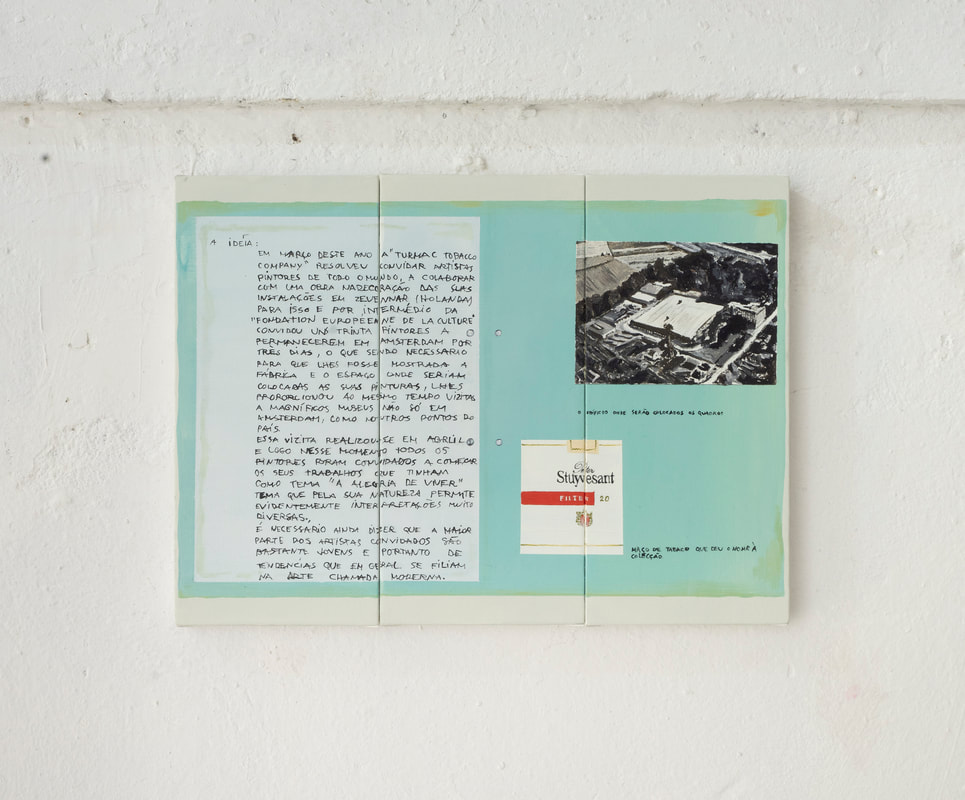

José Escada (1934-1980) was one of the artists commissioned for the Joy of Living project. At 26 years old, he had recently moved to Paris with a Gulbenkian scholarship after being prosecuted by the Portuguese regime over distributing anti-regime hand-outs and signing a rebellious petition. Escada was a proliferous, generous and promising artist; he visited the factory grounds and wrote Gulbenkian a report, dated April 1960. It reads:

«(...) [THE EUROPEAN FOUNDATION FOR CULTURE] INVITED SOME THIRTY PAINTERS TO STAY IN AMSTERDAM FOR THREE DAYS, WHICH WAS NECESSARY TO SHOW THEM THE FACTORY AND THE SPACE WHERE THE PAINTINGS WERE GOING TO (...) RIGHT AT THAT TIME ALL THE PAINTERS WERE INVITED TO BEGIN THEIR WORK THAT HAD “THE JOY OF LIVING”AS A THEME WHICH BY ITS NATURE OBVIOUSLY ALLOWS FOR VERY DIFFERENT INTERPRETATIONS. IT’S NECESSARY TO SAY THAT MOST OF THE INVITED ARTISTS ARE QUITE YOUNG AND THERE- FORE OF TENDENCIES GENERALLY ASCRIBED TO THE NAMED MODERN ARTS.»

Escada went on to paint a watery, lush depiction of colourful flowers in yellow, orange, green and purple in what feels like a magical pollinating paradise. Bridging between figuration and non-figuration, Escada’s oeuvre exempts such definitions, as there are many more fascinating aspects to consider in his lifelong artistic search and experimentation. In conversation with Urbano Tavares Rodrigues for an article in Jornal de Letras e Artes, in 1963, Escada explains that painting always mirrors – and depends on – the social; and “it does so not only through anecdote and allegory but mainly through style and style isn’t planned or predictable. Style is like a day that dawns, it appears almost without us realizing it. We can only check, experimenting and living as intensely as we can, paying attention to everything, because art is made of everything and the style of our painting is also the style of our own life”.

The precise moment in time in which Escada and Stuyvesant crossed paths, under the sign of Joie de Vivre, marked the departure of two long loose lines rolling through out time, both delicately blossoming from Escada’s painterly interpretation of the commission and heading into opposing sides on a symbolic spectrum.

To the Peter Stuyvesant Brand, a possible grasp on the Joy of LivingTM was appropriated for a advertisement identity and image construction, attempting to commercialise pleasure and joy as something that, despite ephemeral, can be repeated and achieved continuously with a gesture as banal as pulling out a cigarette — complemented by skiing in the Alps, fine-dining or travelling to exotic locations. The use of the notion of JoyTM in the cool, sexy and care-free identity of the Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes brand highly contrasts with the socialist mystique of the initial Turmac endeavour; however, it remains intriguing that such a concept stayed on the tip of the Stuyvesant marketing team’s tongue for so long. To José Escada, clues to possible interpretation of the feeling are blatantly exposed - his painting for Turmac is not coy in its kindness and devotion. What Escada does, specifically in style, is the complete opposite of Stuyvesant’s decade-long attempt to commercialise a fleeting indescribable feeling, or to reproduce it. Instead of bottling it up, Escada lays it out, not attempting to prison the feeling, but to make fireworks; like true Joy, the particular appreciation of fireworks comes from its fugitive quality, its imminent disappearance. Those are the things of baffling, crazy beauty.

José Escada returned to Portugal in 1971, struggling constantly with financial instability and becoming sick with tuberculosis in the final years of his life, spending some time in a sanatorium in Caramulo for treatment (beautiful line drawings from this time portray fellow male patients and friends; Escada’s lack of establishment as a queer artist is up for debate). He only enjoyed six years of Portuguese democracy. He worked from his bedroom/studio in his mother’s house, in Alto de Santo Amaro, and turned the window into a projection frame of all emotions, colours and moments he could paint. His later works (1975-1980) are, stylistically, quite different from the multiple moods of his previous work — Diogo told me Escada described it as a “return to the concrete”, which sounds like an urgent matter: what are the graspable images and symbols remaining from a life fully lived?

He was frequently portraying his immediate surroundings, mainly his studio, close people, his two dogs - Strof and Gitano - and the nearby Alto de Santo Amaro viewpoint. He died in 1980, the same year which marks the simmering down of the ever-growing Stuyvesant collection, which had just been agglomerated to the giant British American Tobacco company and was soon to be renamed the BAT Artventure – a mandatory rebranding after European laws prohibited tobacco advertisement.

Corporate initiatives to collect and exhibit art soared in the U.S. and Europe after the 1960’s, taking cue from David Rockefeller’s (Cha- se Manhattan Bank) Art at Work program (1959) and the Turmac project. Usually, the sophisticated, visionary and generous public image of these initiatives and subsequent success narratives relied on the characterisation of the corporate founders as visionary and generous themselves - heroes.Art is not just for the upper-floor offices, it’s also for the people who make the corporate machine move, who carry the bigger weight of underpaid and unexciting labour. Setting aside the strong will to give a critical perspective on centuries-old heroic narratives surrounding white businessmen, the initial Turmac case study offers a glimpse into what I earlier called a happy event, and it certainly wasn’t solely due to the genius of Orlow; it is, instead, the result of close collaboration between private companies and public institutions aligned with Dutch policies of cultural dissemination. And the thing is, factory presidents should absolutely do whatever is in their power to improve employee’s working conditions - which Orlow did, since the workers appreciated the initiative and the production halls became less gloomy.

However, the Stuyvesant Collection and corporate image development is, as we know, a whole other story, reminiscent of a Millennium television ad aired fifteen years ago praising an alternative type of “life worth living” and embodying the worst kind of corporate art collecting and “inspired collector” myth à la Portuguese. In this specific case, the *private* collection is exhibited through a public institution, guarded by dozens of young artists freelancing precariously.I was one of the unhappy freelancers, and so was Diogo - hence the love for corporate art collections.

Diogo painted the ultimate brochures of Joie. Creases divide them three-way, like the one you’re holding. Considering the two introduced simultaneous narratives, one can now face the spoils and profits of each approach to the chase of a fleeting feeling, as Diogo proposes a confrontation of symbolic imagery both from Escada’s beautiful depictions of “concrete” intimate life and Stuyvesant’s publicity, beginning at the first moment of the story in April of 1960.

Mariana Tilly

June 2021

(1) - Quoted from an article on the Wall Street Journal - Colourful Art, from Factory to Auction, 19-2-2010.

La joie de vivre, c’est tant des choses...

Typewriter resting on a rock, the artist takes a break; inhaling Stuyvesant pleasure, exhaling countryside glory. He’s retired; plenty of space to enjoy the golden years. The ad makes a good point though: joy is many, many things. Here’s the scope of it:

In 1960’s spring, the Turmac Tobacco Factory (located in Zevenaar, Netherlands) became the setting of a happy and peculiar event. Paintings were commissioned to emerging European artists within the framework of an experimental cultural project, pushed by semi-public institutions working backstage, and funded by the European Foundation for Culture. The commissioned paintings were to be made specifically to be installed within the factory, and created under the theme Joy of Living. The idea had come from the factory president, Alexander Orlow, who leaded and gave face to the experiment, becoming somewhat of an art-lover socialist hero (imprinting the mythical status ascribed to corporate founders – more on that later – and closely advised by Willem Sandberg, then director of the Stedelijk Museum). The point was not only to bring contemporary art closer to the factory workers, but to improve the environment within the post-war, severe, noisy and industrial production halls where hundreds of workers produced the Peter Stuyvesant Cigarettes. Absolute requirements for the artworks were a considerable size and powerful colouring, in order to “raise spirits of people engaged in monotonous factory work” (1). Indeed, Orlow did an amazing job, and the experiment proved a success - the paintings were dramatically hung in panels from the ceiling of the halls overnight, surprising workers the next morning. Over the following decades, the collection grew into the famed Peter Stuyvesant Collection.

José Escada (1934-1980) was one of the artists commissioned for the Joy of Living project. At 26 years old, he had recently moved to Paris with a Gulbenkian scholarship after being prosecuted by the Portuguese regime over distributing anti-regime hand-outs and signing a rebellious petition. Escada was a proliferous, generous and promising artist; he visited the factory grounds and wrote Gulbenkian a report, dated April 1960. It reads:

«(...) [THE EUROPEAN FOUNDATION FOR CULTURE] INVITED SOME THIRTY PAINTERS TO STAY IN AMSTERDAM FOR THREE DAYS, WHICH WAS NECESSARY TO SHOW THEM THE FACTORY AND THE SPACE WHERE THE PAINTINGS WERE GOING TO (...) RIGHT AT THAT TIME ALL THE PAINTERS WERE INVITED TO BEGIN THEIR WORK THAT HAD “THE JOY OF LIVING”AS A THEME WHICH BY ITS NATURE OBVIOUSLY ALLOWS FOR VERY DIFFERENT INTERPRETATIONS. IT’S NECESSARY TO SAY THAT MOST OF THE INVITED ARTISTS ARE QUITE YOUNG AND THERE- FORE OF TENDENCIES GENERALLY ASCRIBED TO THE NAMED MODERN ARTS.»

Escada went on to paint a watery, lush depiction of colourful flowers in yellow, orange, green and purple in what feels like a magical pollinating paradise. Bridging between figuration and non-figuration, Escada’s oeuvre exempts such definitions, as there are many more fascinating aspects to consider in his lifelong artistic search and experimentation. In conversation with Urbano Tavares Rodrigues for an article in Jornal de Letras e Artes, in 1963, Escada explains that painting always mirrors – and depends on – the social; and “it does so not only through anecdote and allegory but mainly through style and style isn’t planned or predictable. Style is like a day that dawns, it appears almost without us realizing it. We can only check, experimenting and living as intensely as we can, paying attention to everything, because art is made of everything and the style of our painting is also the style of our own life”.

The precise moment in time in which Escada and Stuyvesant crossed paths, under the sign of Joie de Vivre, marked the departure of two long loose lines rolling through out time, both delicately blossoming from Escada’s painterly interpretation of the commission and heading into opposing sides on a symbolic spectrum.

To the Peter Stuyvesant Brand, a possible grasp on the Joy of LivingTM was appropriated for a advertisement identity and image construction, attempting to commercialise pleasure and joy as something that, despite ephemeral, can be repeated and achieved continuously with a gesture as banal as pulling out a cigarette — complemented by skiing in the Alps, fine-dining or travelling to exotic locations. The use of the notion of JoyTM in the cool, sexy and care-free identity of the Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes brand highly contrasts with the socialist mystique of the initial Turmac endeavour; however, it remains intriguing that such a concept stayed on the tip of the Stuyvesant marketing team’s tongue for so long. To José Escada, clues to possible interpretation of the feeling are blatantly exposed - his painting for Turmac is not coy in its kindness and devotion. What Escada does, specifically in style, is the complete opposite of Stuyvesant’s decade-long attempt to commercialise a fleeting indescribable feeling, or to reproduce it. Instead of bottling it up, Escada lays it out, not attempting to prison the feeling, but to make fireworks; like true Joy, the particular appreciation of fireworks comes from its fugitive quality, its imminent disappearance. Those are the things of baffling, crazy beauty.

José Escada returned to Portugal in 1971, struggling constantly with financial instability and becoming sick with tuberculosis in the final years of his life, spending some time in a sanatorium in Caramulo for treatment (beautiful line drawings from this time portray fellow male patients and friends; Escada’s lack of establishment as a queer artist is up for debate). He only enjoyed six years of Portuguese democracy. He worked from his bedroom/studio in his mother’s house, in Alto de Santo Amaro, and turned the window into a projection frame of all emotions, colours and moments he could paint. His later works (1975-1980) are, stylistically, quite different from the multiple moods of his previous work — Diogo told me Escada described it as a “return to the concrete”, which sounds like an urgent matter: what are the graspable images and symbols remaining from a life fully lived?

He was frequently portraying his immediate surroundings, mainly his studio, close people, his two dogs - Strof and Gitano - and the nearby Alto de Santo Amaro viewpoint. He died in 1980, the same year which marks the simmering down of the ever-growing Stuyvesant collection, which had just been agglomerated to the giant British American Tobacco company and was soon to be renamed the BAT Artventure – a mandatory rebranding after European laws prohibited tobacco advertisement.

Corporate initiatives to collect and exhibit art soared in the U.S. and Europe after the 1960’s, taking cue from David Rockefeller’s (Cha- se Manhattan Bank) Art at Work program (1959) and the Turmac project. Usually, the sophisticated, visionary and generous public image of these initiatives and subsequent success narratives relied on the characterisation of the corporate founders as visionary and generous themselves - heroes.Art is not just for the upper-floor offices, it’s also for the people who make the corporate machine move, who carry the bigger weight of underpaid and unexciting labour. Setting aside the strong will to give a critical perspective on centuries-old heroic narratives surrounding white businessmen, the initial Turmac case study offers a glimpse into what I earlier called a happy event, and it certainly wasn’t solely due to the genius of Orlow; it is, instead, the result of close collaboration between private companies and public institutions aligned with Dutch policies of cultural dissemination. And the thing is, factory presidents should absolutely do whatever is in their power to improve employee’s working conditions - which Orlow did, since the workers appreciated the initiative and the production halls became less gloomy.

However, the Stuyvesant Collection and corporate image development is, as we know, a whole other story, reminiscent of a Millennium television ad aired fifteen years ago praising an alternative type of “life worth living” and embodying the worst kind of corporate art collecting and “inspired collector” myth à la Portuguese. In this specific case, the *private* collection is exhibited through a public institution, guarded by dozens of young artists freelancing precariously.I was one of the unhappy freelancers, and so was Diogo - hence the love for corporate art collections.

Diogo painted the ultimate brochures of Joie. Creases divide them three-way, like the one you’re holding. Considering the two introduced simultaneous narratives, one can now face the spoils and profits of each approach to the chase of a fleeting feeling, as Diogo proposes a confrontation of symbolic imagery both from Escada’s beautiful depictions of “concrete” intimate life and Stuyvesant’s publicity, beginning at the first moment of the story in April of 1960.

Mariana Tilly

June 2021

(1) - Quoted from an article on the Wall Street Journal - Colourful Art, from Factory to Auction, 19-2-2010.